Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam: Africa’s Most Controversial Dam

Ethiopia, a landlocked country with a history dating back millions of years, is building Africa’s Largest Hydropower Dam, with a reservoir larger than the city of London. This dam is expected to alleviate the country’s power crises and double Ethiopia’s power generation capacity, providing clean and renewable energy to millions in the region.

However, this dam faces criticism, primarily due to its location on the Blue Nile, a major tributary of the Nile River – a critical water source for both Sudan and Egypt. Tensions arose after the dam’s filling began; Egypt declared that it would not tolerate any actions that reduce its share of the Nile’s water. If tensions escalate further, the possibility of military conflict remains a concern.

Today, we take a closer look at Africa’s most controversial megaproject to determine whether it will solve Ethiopia’s power issues or exacerbate regional tensions.

Ethiopia’s Energy Crisis

Emerging from an unstable and tumultuous past, marred by colonialism and civil war, Ethiopia has managed to significantly grow its economy in the last two decades. Despite this remarkable economic progress, the country continues to face severe humanitarian challenges. A key factor contributing to these challenges is the ongoing civil war in the Tigray region. Furthermore, the situation is exacerbated by the fact that approximately half of the population lacks access to electricity. This lack of energy access has led to frequent power interruptions and shortages. As Ethiopia’s population and economy continue to grow, meeting the energy demands of the nation becomes an increasingly formidable task, highlighting the urgent need for sustainable and robust energy solutions.

Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD)

Ethiopia is making significant strides in solving its energy crisis with the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), a centerpiece of its energy strategy. The Office of National Coordination in Ethiopia recently announced that this hydroelectric power dam is now 90% Complete. Once fully operational, the dam is expected to generate up to 6,500 Megawatts of electricity, effectively doubling the country’s annual national electricity output. This increase in power generation is crucial for Ethiopia, where currently only half of its 120 Million Population has access to electricity. The completion of the GERD will enable the 60% Of the Population not yet connected to the grid to gain access to reliable power.

Also Read: Why Russia Is Not Happy with Europe’s Vistula Spit Canal

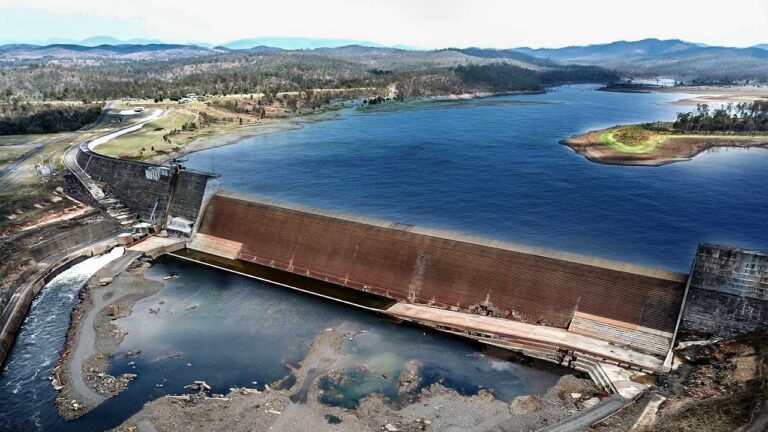

The GERD, standing at a remarkable height of 145 meters (476 feet) and stretching 1.8 Kilometers (1.1 Miles) Long, is not just Ethiopia’s largest infrastructure project but also a transformative step for its future. This huge hydroelectric dam, upon completion, is set to produce over 5,000 Megawatts of electricity, a feat that will double the country’s electrical production. The dam, located on the Blue Nile River in the Benishangul-Gumuz Region, near the Sudanese border, has been under construction since 2011. Despite financial challenges and limited international funding, Ethiopia managed to finance this $5 Billion project primarily through internal sources and bond sales. Of the total cost, $1 Billion Dollars for turbines and electrical equipment was funded by the Exim Bank of China. The dam, apart from solving Ethiopia’s longstanding power shortage, also presents an opportunity for Ethiopia to export electricity to neighboring countries like Djibouti, Sudan, Uganda, and Kenya, boosting regional energy security.

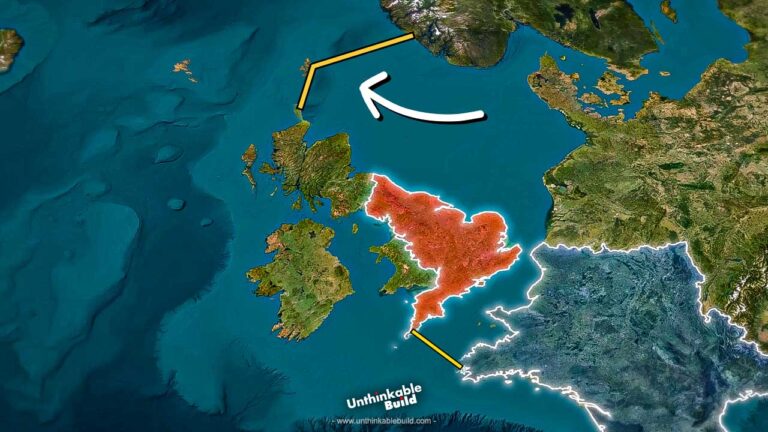

A significant aspect of the GERD’s completion involves filling its vast reservoir, which has a volume of 74 Cubic Kilometers. The filling process is a lengthy one, already taking more than two years and potentially extending up to seven years. This process is critical, as the reservoir’s capacity exceeds the annual flow of the Blue Nile. The successful completion of this project represents a pivotal moment for Ethiopia, marking a transition towards sustainable and robust energy solutions for its growing population and economy.

GERD Design

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) has undergone several design changes since its inception in 2011, affecting its electrical output and storage capabilities. Originally, the hydropower plant was planned to have 15 Generating Units, each with a capacity of 350 MW, totaling an installed capacity of 5,250 MW and an expected annual power generation of 15,128 GWh. However, this plan was later revised to increase the capacity to 6,000 MW with 16 Generating Units of 375 MW each, and an expected generation of 15,692 GWh per year. In 2017, the design was altered again, adding 450 MW for a total of 6,450 MW, achieved by upgrading 14 of the 16 units from 375 MW to 400 MW.

Storage parameters of the dam also evolved. Initially, the dam was to be 145 Meters Tall with a 66 km3 reservoir and a 1,680 km2 surface area. In 2013, an Independent Panel of Experts (IPoE) recommended changes, increasing the reservoir size to 74 km3 and the surface area to 1,874 km2. These dimensions have remained since. The dam’s design includes accommodating higher water flows in case of extreme floods, increasing the main dam height to 155 Meters and the adjacent rock-filled saddle dam to 50 Meters.

As of August 2017, the GERD features two dams: the main gravity dam at a height of about 500 meters above sea level and a 50-Meter High rock-fill saddle dam. The reservoir behind these dams will have a storage capacity of 74 km3 and a surface area of 1,874 km2 at full supply level. Hydropower generation will occur between reservoir levels of 590 Meters and 640 Meters. The dam also includes 3 Spillways designed to handle extreme flood events.

These design changes reflect the dynamic nature of such a large-scale infrastructure project, with adjustments made to optimize power generation and manage the complex hydrological aspects of the Nile River.

GERD’s Regional Implications

Egypt, an early critic of the GERD project, maintains its stance, fearing that the dam will severely jeopardize its water supply. This concern is not unwarranted, given that around 97% of Egypt’s 106 Million Population reside along the banks of the Nile and rely heavily on it for fresh water. The Nile’s significance to Egypt transcends practical needs; it is deeply embedded in the nation’s identity and history, having been a lifeline since ancient times.

The GERD, positioned over 2000 Kilometers upstream from Egypt, is viewed as an “existential threat.” Historically, the Nile has been central to Egypt’s development from an advanced ancient civilization to a modern African powerhouse. The government has responded to the potential water loss from the GERD’s reservoir filling (which started in 2020) by redirecting more water from Lake Nasser, the reservoir of Egypt’s Aswan High Dam, into the Nile. However, this measure might not fully mitigate the impact of the GERD on Egypt’s water supply.

Also Read: Navi Mumbai Airport: A Game-Changer for India

Egypt’s fear is understandable considering that 97% of its Freshwater comes from the Nile, and the per capita annual water share is a mere 590 cubic meters. The construction and filling of the GERD reservoir pose significant risks for Egyptians, for whom the Nile is not just a water source but a symbol of survival.

The situation is similarly precarious for Sudan, which also depends on the Nile for its agricultural and economic needs. The prospect of Ethiopia controlling the flow of the Nile is seen as a direct threat to the political and existential stability of both Egypt and Sudan. These nations are keen on being involved in decisions regarding the operation of the dam, especially concerning the timing and duration of opening or closing the floodgates to prevent issues like excessive evaporation and downstream flooding.

Tensions Escalated with the Filling of the Dam

Tensions among Ethiopia, Egypt, and Sudan escalated in July 2020 when Ethiopia commenced the filling of the dam. This development underscores the complex interplay of geopolitics, survival, and environmental management in the Nile basin. The resolution of these tensions will require careful negotiation, respecting the needs and concerns of all parties involved, while acknowledging the vital role the Nile plays in the region’s ecosystem and the livelihoods of millions.

With the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) now 90% Complete, the geopolitical landscape of the Nile Basin is shifting. Interestingly, Sudan has evolved from skepticism to support for the project. However, Egypt remains critical, fearing a potential reduction in Nile water flow. Despite these tensions, experts, including Timothy Kaldas from the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy, suggest that a military conflict over the dam is unlikely, mainly because attacking the dam now would cause massive flooding in Sudan’s Blue Nile River.

Egypt has accused Ethiopia of undermining trilateral efforts involving Egypt, Sudan, and the United Nations to reach a mutual agreement. They claim Ethiopia’s actions violate the 2015 Declaration of Principles, which requires consultation among the signatories before undertaking Nile River projects. Despite occasional threats of military action by Egypt, the likelihood of armed conflict has diminished since August this year. Both Egypt and Sudan are now calling for UN intervention to mediate negotiations, but cooperation seems distant as mutual accusations continue.

Scientific Solutions

However, there’s a silver lining in this complex scenario. If managed correctly, the GERD could offer significant benefits to the entire region, including Egypt and Sudan. It has the potential to regulate massive flooding in downstream countries and facilitate the equitable distribution of water, benefiting the dams within these nations. Additionally, the energy generated by the GERD could be a boon for the entire region.

Experts suggest that political and scientific solutions are feasible. They recommend a data-sharing agreement between Ethiopia, Egypt, and Sudan to manage water flows from the dam, including guaranteed releases during droughts. This approach could foster trust and enable sustainable, multilateral management of the Nile’s flows.

There’s also potential for greater benefits if Egypt’s Aswan High Dam and Ethiopia’s GERD were operated in tandem. Given the GERD’s highland location and lower temperatures compared to the Aswan High Dam in Lake Nasser, sensible management could lead to lower evaporation losses. This means both countries could have more water for hydropower generation.

As the GERD nears completion, expected between 2024 and 2025, the hope for an agreement lingers. The situation remains fluid, with rainfall patterns potentially influencing the project’s timeline. The coming years will be crucial in determining how these three nations navigate their shared reliance on the Nile, balancing national interests with regional stability and cooperation.