Chinese Maglev Hyperloop Train Will Travel at 1000 Km/h

At the beginning of the 21st century, China had slow and often uncomfortable trains across the country, with low average speeds and no signs of high-speed railways. But today, the picture is completely different. Since 2008, the world’s most populous nation has built the world’s largest network of high-speed railways. Additionally, China is expected to launch a hyperloop – an ultra-high-speed pipeline maglev system – by 2035. This 150km-long in-vacuum tunnel aims to enable maglev trains to travel at speeds of up to 1,000km/h.

Currently, China has approximately 42,000 Km of railway lines crisscrossing the country, linking all of its major megacities. Impressively, half of the total network was completed in just the last five years. China plans to double the length of its existing railway network to approximately 70,000 Km by 2035. By 2020, 75% of Chinese cities with a population of 500,000 or more had high-speed rail links, with maximum speeds of 350 kph (217 mph) on many lines. This development has transformed intercity travel and broken the dominance of airlines on the busiest routes.

In comparison, Spain, which has the most extensive high-speed network in Europe and occupies the second place in the global league table, has just over 2,000 miles of dedicated lines built for operation at over 250 kph. In contrast, the UK has only 107 Km of such networks. Another surprising fact is that the United States has only one route that qualifies for high-speed status and that is Amtrak’s North East Corridor. where Acela trains currently reach top speeds of 240 kph on expensively rebuilt sections of line shared with commuter and freight trains.

Let’s find out how China is building the country’s first hyperloop train line between Shanghai and Hangzhou, with a 150km long tunnel.

Also Read: Vietnam’s $65 BN North-South Express Railway

The concept of an ultra-high-speed pipeline maglev system, widely known as a hyperloop or hyperloop train, gained prominence in modern engineering thanks to Elon Musk in 2012. Yet, its roots trace back to 1799, when George Medhurst, an Englishman, envisioned a vactrain capable of speeds between 6,400 – 8,000 km/h (4,000–5,000 mph), surpassing the speed of sound by five to six times. It was American engineer Robert Goddard who actualized this concept in 1904.

Elon Musk established The Boring Company in December 2016 to turn his idea into reality. Following Musk’s lead, Richard Branson, the founder of the Virgin Group, entered the field with his own hyperloop venture, named Virgin Hyperloop One. Eight years after Elon Musk first proposed the idea of this futuristic mode of transportation, human passengers have traveled in a hyperloop pod built by Virgin Hyperloop. The maiden voyage occurred on a 500 meter section of test track outside Las Vegas and lasted just 15 seconds. Since their inception, both companies have faced technical challenges and financial burdens. Reportedly, Virgin Hyperloop One has laid off more than 100 employees and abandoned the idea of transporting humans, while The Boring Company dismantled its test tunnel last year.

China entered the hyperloop train race later than others; however, it took the project team less than a year to complete its first test run after construction began. In October 2022, researchers at the North University of China successfully completed a test of a Hyperloop train system in Datong, Shanxi province.

Notably, China currently operates the world’s largest high-speed rail network, spanning over 26,000 miles (42,000km). The Chinese government has ambitious plans to increase the maximum speed of its existing train network to 248 mph (400 km/h) within the next two years.

China has been heavily investing in hyperloop technology. In October 2022, the country achieved a significant milestone by successfully testing a Hyperloop train system that operates in a low vacuum environment inside a tube. This achievement marked the first ‘full-scale and full-process integrated test’ of such a system, with a maglev train reaching speeds of up to 81 mph (130 km/h). The current test tube, measuring only 1.24 miles (2 Km), is slated to be extended to 37 miles (60 Km) in the coming years. The goal is to eventually transport passengers and cargo at speeds of 621 mph (1,000 km/h) or faster in a near-vacuum tube.

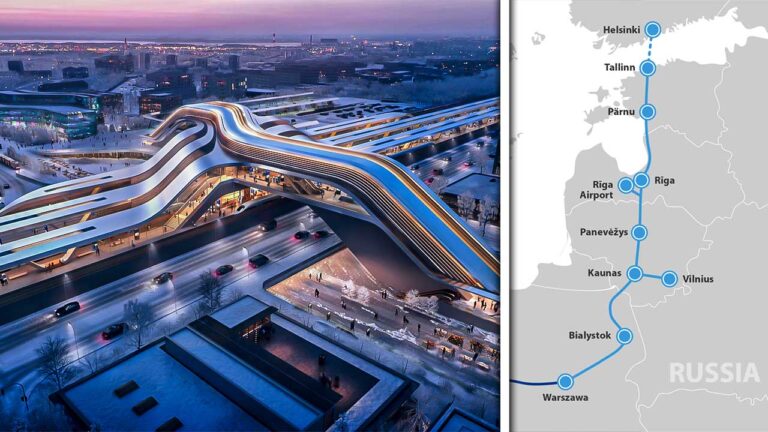

Several potential routes for China’s hyperloop Train system have been under consideration by researchers, including connections between Beijing and Shijiazhuang, Chengdu and Chongqing, and Guangzhou and Shenzhen. A proposed route linking Beijing with Shijiazhuang could unite China’s capital with the capital of Hebei province in the north, while a route between Guangzhou and Shenzhen would enhance connectivity in the Pearl River Delta area. The route between Chengdu and Chongqing is poised to improve transport in China’s western regions.

Also Read: Building the New Saudi Arabia: Vision 2030’s Saudi Mega Projects

In choosing the inaugural hyperloop line, project experts are evaluating various aspects such as the population density, economic vitality, and existing transportation networks in the involved areas.

Currently, a road journey between Shanghai and Hangzhou, spanning 175 Km, takes about three hours. The hyperloop system, once operational, could dramatically reduce this travel time to just 15 minutes.

However, before the inaugural journey can occur between these cities, significant infrastructure development is required. This includes the construction of low-pressure tubes, specialized stations, and comprehensive safety and regulatory frameworks.

In a maglev system, two sets of electromagnets play crucial roles: one set lifts the train off the track through repulsion, while the other propels the floating train forward, leveraging the absence of friction. These trains hover about 10 cm (3.9 inches) above the track.

Globally, six commercial maglev systems are operational, with one in Japan, two in South Korea, and three in China.

The hyperloop concept, however, introduces a more complex challenge. Engineers are still grappling with the task of maintaining a vacuum over extensive distances, a hurdle that has so far hindered the hyperloop from becoming a tangible reality.

China’s vast size and diverse landscape, encompassing varying terrains, geologies, and climates, have posed significant challenges to its railway engineers. These engineers have adeptly navigated through different environments, from the freezing conditions of Harbin in the north to the humid climate of the Pearl River Delta, and across the Gobi Desert via the 1,776 km Lanzhou-Urumqi line.

This rapid expansion in railway infrastructure, facilitated by centralized state funding and streamlined planning, has come with its drawbacks. Notably, the construction of new lines often overlooks the impact on existing communities along their paths.

One of the most notable setbacks in China’s high-speed rail development was the Wenzhou collision in July 2011. This tragic accident, involving the collision and derailment of two trains, resulted in 40 fatalities and nearly 200 injuries, leading to a nationwide speed reduction and a temporary halt in new rail construction until an official investigation was completed. Despite this, the following decade saw no major incidents, and the network’s expansion continued alongside a significant rise in passenger numbers.

The scale of China’s railway projects is staggering. For instance, the Zhengzhou East-Wangzhou line, stretching 815 Km and costing $13.5 billion, was completed in less than five years. The opening of the 180 Km Xuzhou-Lianyungang line in February created an unbroken 3,490 Km high-speed rail link, allowing trains to cover the Beijing-Harbin route of 1,700 Km in just 5 hours.

By the end of 2020, China National Railways was operating over 9,600 high-speed trains daily, including unique high-speed overnight sleeper services on some longer routes. Many of these high-speed lines feature extensive elevated sections, covering more than 80% of some routes, to navigate densely populated urban areas and agricultural lands. The network also boasts over 100 tunnels, each exceeding 10 kilometers, and impressive long-span bridges crossing major natural barriers like the Yangtze River.

China aims to establish high-speed rail as the preferred option for long-distance domestic travel, but the impact of these railways extends far beyond transportation. Mirroring the significance of Japan’s Shinkansen in the 1960s, China’s high-speed rail network is a testament to its economic strength, swift modernization, technological advancement, and increasing prosperity.

For the Communist Party of China and its leader, Xi Jinping, high-speed rail serves as a strategic instrument for promoting social unity, extending political influence, and integrating culturally diverse regions into a unified national framework.

In this respect, China’s approach echoes the historical use of railways. Like the early railroads in North America, Europe, and the European colonies, China’s high-speed rail network is driven by similar ambitions. The development of railways in countries such as Russia (with the iconic Trans-Siberian Railway), Prussia, France, Italy, and within the British Empire, was propelled by political, military, and economic motives.

However, China is accomplishing in just a few years what took decades to achieve in the 19th and early 20th centuries, demonstrating the accelerated pace of its railway expansion.